Detroit Auto Show 2016: Obama Touts Car Industry Rebound As Autoworkers Face Pressure From Low-Cost Competitors, Looming Sales Plateau

When he spoke in Detroit on Wednesday having toured the city's auto show, President Barack Obama touted the recent successes of the U.S. auto industry. And in many respects, he was right to do so: When Obama was preparing to take office in late 2008 the economy was struggling and General Motors, the nation’s largest automaker, was on the brink of ruin. Since then, the industry has recovered, thanks to financial help and restructuring rounds.

Sectorwide employment has grown by 640,000 since the auto industry bailouts of 2009. Tens of thousands of workers just won solid pay raises in their latest round of contract negotiations, and auto sales are the highest they’ve ever been.

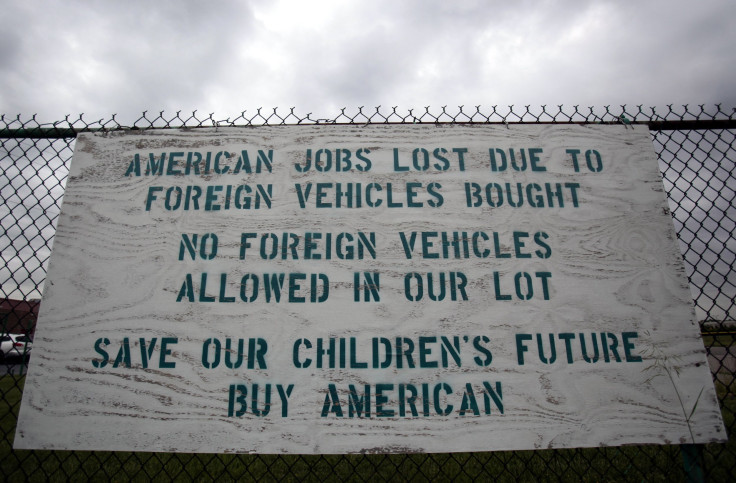

But there’s reason for pessimism, too. Employees at the foreign-owned manufacturers, largely based in the U.S. South, aren’t seeing the sorts of wage gains promised to their counterparts at Ford, General Motors and Fiat Chrysler Automobiles. Outsourcing pressures from Mexico are mounting. And eventually — though it remains unclear exactly when — sales will dip, cutting off job growth.

“Folks are looking over their shoulders, asking, ‘When will the music stop?’ ” said Mike Wall, automotive analyst at IHS Inc. “Where are we in the cycle?”

Near a plateau, by the looks of it: Last year, Americans bought 17.5 million cars and trucks, smashing a record set in 2000 and extending a growth spurt that dates back to 2009, when consumers bought just 10.4 million vehicles. Tapering sales will eventually put a lid on employment growth and may well translate into some modest amount of layoffs.

Such is the nature of a cyclical industry. “What goes up must come down,” said Kristin Dziczek, director of the industry and labor group at the Michigan-based Center for Automotive Research.

Last summer, the United Auto Workers secured one of its strongest contracts for workers at the Big Three in recent memory. Covering 140,000 workers at Ford, GM and Fiat Chrysler Automobiles, mostly scattered across the industry’s Midwestern heartland, the deals are slated to phase out so-called second-tier wage rates for new and recent hires. Of course, not every worker in the industry benefits.

Many parts suppliers were not covered by the deals. Nor were the foreign-owned assembly plants that are largely concentrated in the South — places like Volkswagen’s factory in Chattanooga, Tennessee, Nissan’s plant in suburban Jackson, Mississippi, or the Mercedes-Benz facility on the outskirts of Tuscaloosa, Alabama. The latter bunch tend to rely on temporary workers.

“In the nonunion sector, wages are really low,” said UAW Vice President Cindy Estrada. “The foreign transplants, they may look like they’re paying the same as us, but when you look at the temporary workers, they’re not. I mean, most temporary workers are making $12 an hour with no chance of a job in the middle class.”

Officials with Nissan and Mercedes declined to disclose information about the respective sizes of their temporary workforces or their average pay rates. Volkswagen did not respond to a request for comment.

From steelmaking to refrigerator production, outsourcing has long plagued American manufacturing workers. Today, Mexico is the main source of jitters for autoworkers. With the exception of Volvo’s recent announcement that it was headed to South Carolina — a state with one of the lowest union membership rates in the nation — every North American auto plant sited since 2009 is in Mexico. “There’s always going to be somebody who can do it cheaper,” Dziczek said.

That’s in large part due to cheaper labor costs. According to numbers provided by Dziczek, the difference in worker costs between a single Ford Fusion produced in Michigan and one made in Hermosillo, Mexico, is $600.

But automakers are also drawn toward Mexico’s free-trade agreements, which cover 45 countries, compared to 20 for the United States. “It makes for a compelling springboard into the global market,” said Mike Wall, the analyst from IHS.

The North American Free Trade Agreement ensures easy access into the United States, where about two-thirds of Mexican auto exports flow. Comparable deals with Europe and Latin America give Mexico a further cost advantage over the United States.

Industry observers predict auto production in Mexico will continue to grow in coming years.

Adding to these pressures are a handful of long-term concerns: For one, automakers are grappling with new environmental regulations, Dziczek said. As Bloomberg reported Wednesday, Fiat Chrysler has particularly struggled to reduce carbon emissions and improve fuel economy in accordance with new rules from the Environmental Protection Agency. The company’s CEO, Sergio Marchionne, has described the mandates as an existential threat.

Meanwhile, models of ownership are evolving. Auto industry executives and insiders are closely watching the rise of ride-sharing and ride-hailing services like Uber and Lyft. Then there’s the question of automation, a prospect highlighted by Google’s driverless cars. Wall said he doesn’t expect the production of fully autonomous vehicles on a significant scale to begin until 2035.

Moreover, as more Americans move to cities — bastions of congested streets, public transit and easily available ride-hailing services — Wall said that could weigh on sales.

“We’re probably the most vehicle-dense society in the world,” he said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.